When French author Jules Verne wrote From the Earth to the Moon (1865), Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (1869) and Around the Moon (1870), space flight was merely an idea and underwater breathing was so new that physiologists still didn’t know what causes decompression sickness. Many dismissed his novels as surreal impossibilities merely grounded in fantasy, yet within about 100 years, human kind had realized his visions.

But beyond this, a century before the first humans left Earth, Verne began the special connection between space and sea exploration by writing about both. The similarities and overlap in space travel and undersea exploration, at least on one level, explain the connection:

- We need life support for anything more than a brief visit.

- Technology protects us, head-to-toe and we need it to breathe, see, avoid thermal stresses, move effectively and more.

- Pressure changes require us to manage DCS risk (among other effects).

- We share the experience of “weightlessness” (technically, microgravity and neutral buoyancy, respectively) which can only be accomplished (for more than a few seconds) by going into space or underwater.

- The degree and complexity differ, but we need specialized training to explore both environments.

Considering this, it’s hardly surprising that most astronauts are divers. Since the 1960s, they have practiced spacewalks underwater and today do so as a regular part of mission training in the NASA Neutral Buoyancy Lab, ESA Neutral Buoyancy Facility and similar facilities at other international space agencies. In 1965, Mercury astronaut Scott Carpenter (sixth person in space, fourth to orbit the Earth in 1962) became the first aquastronaut (someone who has flown in space and lived underwater in an ambient pressure habitat) by spending 28 days undersea in the US Navy’s Sealab II project.

Over the years, countless studies by the space community, ranging from decompression studies and equipment oxygen compatibility to the use of EANx and altitude exposure, have benefitted us as divers. Likewise, the space community has similarly applied diving’s research to its needs.

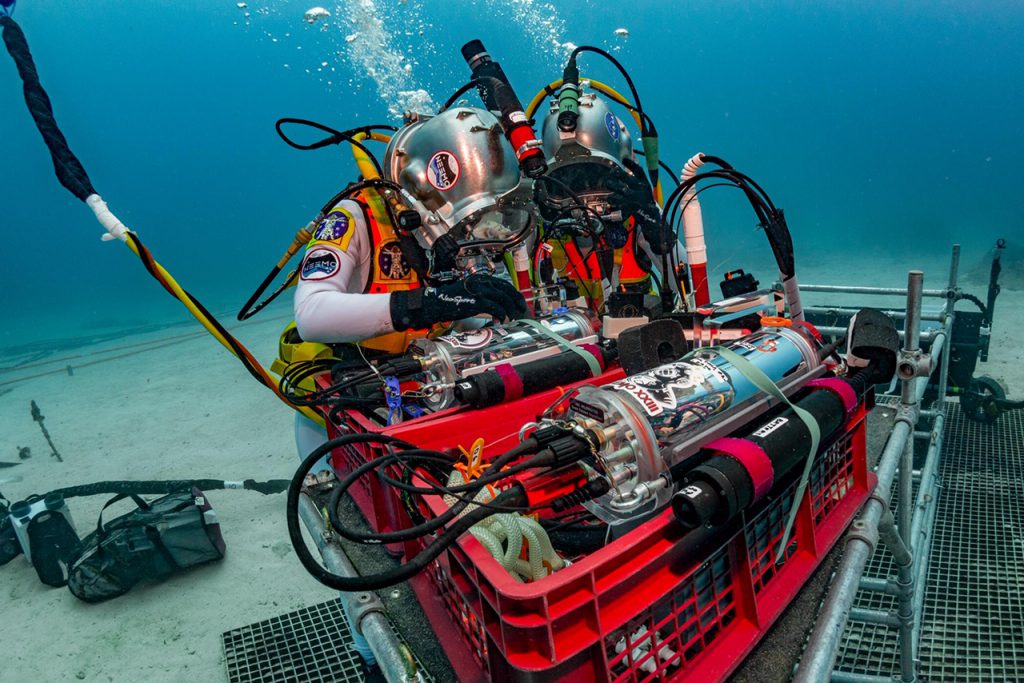

Today, it is probably the NASA NEEMO project that most exemplifies the sea and space connection. Since 2001, NEEMO has been using the Aquarius underwater habitat in the U.S. Florida Keys for analog space missions. During NEEMO missions, astronaut/NASA scientist crews live underwater (typically for a week) in saturation and conduct research specific to spaceflight – but on these missions they’re divers. So, NEEMO crews also research marine life, study water flow, plant coral and carry out other oceanography in ways that integrate with learning about human spaceflight.

In bridging the gap between sea and space, NEEMO highlights that the real connection astronauts and divers share is not in the technology and extreme environments. The connection is us. We may not get to be both divers and astronauts, but in our hearts many of us are both. We love going where few people (relatively speaking) go. Curiosity, challenge, and at least a little techno philia drive us, and we want to make a difference, in a different place, and in different ways. Something separates us from those content to be land-bound/Earth-bound, and it drives us to be divers and astronauts.

The reality is that for many people (including me), what keeps us from space isn’t desire, but access. So far, fewer than 600 people have gone there. It takes a lot to become an astronaut and while space tourism is on the rise, for the foreseeable future it will be very expensive. Outer space is open to, at most, dozens of people.

But, inner space is accessible to almost anyone (baring medical/psychological restrictions) who wants to go there. And despite this access, being a diver is just as extraordinary and just as much a privilege as being an astronaut. Yes, millions of people are certified divers, but that’s still less than one percent of the world’s population who have tried diving. There are millions more who want to go, or would want to, and we can help them – for their sake, and the sake of the seas themselves.

More than 150 years ago, Jules Verne reminded us the sea is a special, important place and that you and I should never think that visiting it is ordinary, nor take it for granted. “The sea is everything,” he wrote in Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea. “It covers seven-tenths of the terrestrial globe. Its breath is pure and healthy. It is an immense desert, where [people are] never lonely, for [they] feel life stirring on all sides.”

Dr. Drew Richardson

PADI President & CEO