On the East African coast, coral reefs extend from the Red Sea to Madagascar. At low tides they reveal themselves beneath a wash of foam, where they form a breakwater for the fair white beaches that gild much of the shoreline. About half way along this chain of biodiversity sits the Archipelago of Zanzibar.

The largest of its islands, Unguja, has been a major historical port and a launch pad from the African interior for trade. In the mid 19th century it was a stepping stone from Europe to the lands of the Orient, and its history is knotted with the colonial occupations of the Omani Arabs and the British. The streets of its capital, Stonetown, are stark with reminders of the islands past, where crumbling edifices of Islamic architecture sit next to colonial coffee houses.

We dropped anchor just off the reef, where the crew of a small fishing boat made ready their nets.

We boarded a motorized wooden Dhow from the beach. In the evening its traditional counterparts hoist their elegant sails for sunset cruises on the Indian Ocean. Our boat was headed for Bawe, one of a few sandy islands within a short distance from the centre of town. We dropped anchor just off the reef, where the crew of a small fishing boat made ready their nets.

Hassan was my buddy for the day, and we stepped overboard in search of the wreck of the Royal Navy Lighter, a scuttled barge that rests at 30m. We descended past the reef and then set a compass course for the wreck. Swimming for about ten minutes across a sandy bottom, its ghostly shape emerged as a lumpy haze in the otherwise crystal water.

Visibility was excellent but as we drew near a translucent wall blocked our path, where a fishing net formed a barrier that travelled as far as we could see in either direction. Above us it rose for about ten metres. I went to lift the net so that we might pass beneath it, but Hassan indicated that we were going over the top. We both carried knives, but any interference with the net might result with an angry fisherman reprimanding us thirty metres below.

As fish populations are depleted, fishermen are resorting to more extreme methods. They will dive with basic SCUBA equipment, usually a dive bottle and regulator strapped to their back with rope. They have little to no training and regularly end up in the islands decompression chamber, which is there to serve their specific purpose. Perhaps the most jarring of fishing practices is the use of dynamite, which not only decimates fish populations but blows devastating craters in the reef. Stone Town is famous for its night markets, where visitors can indulge in an array of grilled fish, but it comes at a cost.

On the other side of the net we found a spear gun, abandoned on the sea floor. The ship itself had been used to transfer equipment to and from the British warships anchored in the harbour in the 40s and 50s. Inside the forward hatch we found an old receptacle and mounting brackets for cylinders of acetylene gas, which was used to fuel the ships lights when it served as a lighting vessel. The wreck has been well claimed by the ocean, with corals and seaweed growing on the hull and sparse superstructure.

The whole escapade would call for a cautious ascent and a reasonable decompression stop

As time dictated that our stint on the wreck was drawing to a close, the fishing net began to drag. We ascended once again to cross, dive computer screeching as we reached the top and then descended to the other side. The whole escapade would call for a cautious ascent and a reasonable decompression stop. Fortunately the reef which surrounds Bawe island sat at the perfect depth to be explored while our bodies adjusted for our safe return to the surface.

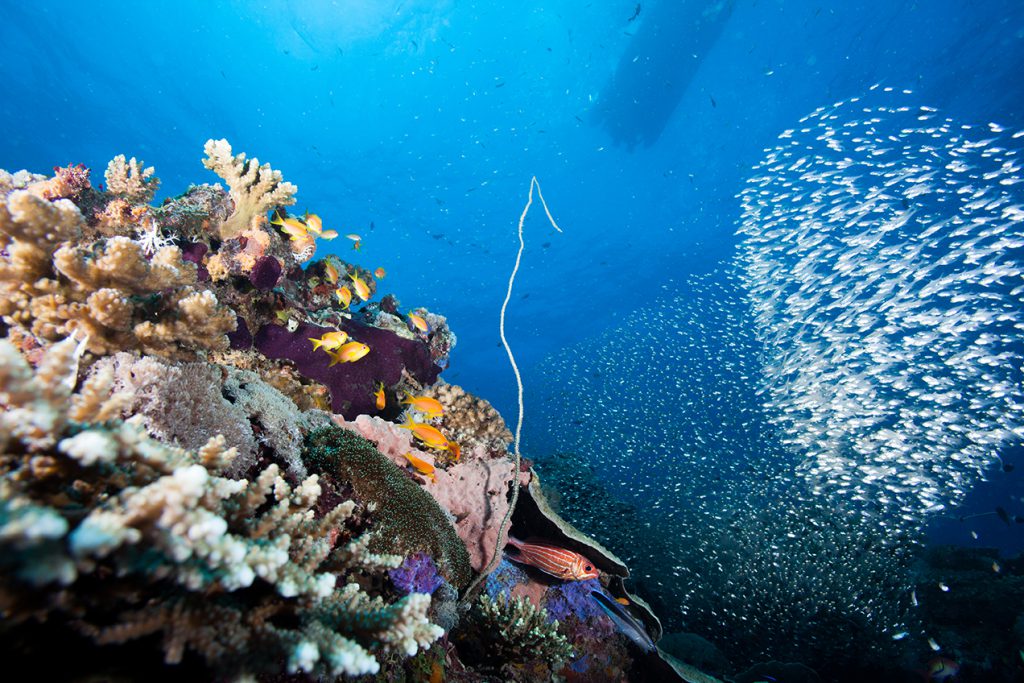

The long shallow reef is dense with corals, which provide a vibrant contrast to the sandy bottom around the wreck. Anemone fish inspected the glare of our masks, while parrot fish and trigger fish wove through coral bommies. Leaf fish and pipe fish are among the array of life which inhabits this spot. Fishing has taken its toll, although I am wary of holding fishermen to account as they make a living by feeding a market driven by consumption.

In 2014 a team of scientists and divers surveyed the entire network of coral reefs from South Africa, through Zanzibar, to Kenya. They found that certain well-established no-take zones were effective in protecting important species, but less large predatory fish and an increase in algal cover showed that herbivorous fish were being over-exploited.

The reefs are further threatened by sediment and pollutant runoff from rivers, and damage from careless diving and snorkeling practices. A particularly severe El Nino in 1997/98 destroyed about 90% of the East African reef corals, in what might be perceived as a premonition for the effects of human-induced climate change. The centre I was diving with, The Zanzibar Dive Shop, One Ocean, prides itself on being a socially responsible and environmentally friendly dive operation, practising respectful diving and engaging with coastal communities and NGO’s.

Juvenile white tipped reef sharks frequent the area, and green sea turtles lay their eggs on the islands beach

Further north, and on the east coast of Unguja, is a marine conservation area which surrounds Mnemba Island. The numbers of fish here were significantly higher than at my first dive site, although the coral reef was not as spectacular as the one at Bawe. This begs the question, how much life would inhabit the reef at Bawe were it not pillaged by fishermen?

Mnemba island is a popular destination for both diving and snorkeling. From Matemwe beach we motored out in a large wooden dhow, following the coast until we reached a gap in the reef which shoulders the east side of Unguja. Beneath the surface, moray eels snapped from the holes in which they ominously lurked, while groupers and lion fish were a more pleasant sight to encounter.

Drifting in a gentle current, we caught glances of parrot fish, yellow snapper, scorpion fish and goat fish, to name a few. Although none were spotted on this particular day, juvenile white tipped reef sharks frequent the area, and green sea turtles lay their eggs on the islands beach between February and September.

For Zanzibar’s most famous visitor you will have to visit between October and March. During this period Whale Sharks can be sighted, but are more frequently found on the southern island of Mafia, which can be accessed by plane or ferry.

Unguja is close to the Tanzanian coast, so with its west coast facing the mainland and the east pointing out to sea, the island provides an array of dive locations. Paired with the opportunity to immerse yourself in the beauty of an island steeped in a unique social history, it makes for a place that gleams in the memory of any traveller so that they will surely be drawn to return.

Learn more about diving in Zanzibar on the blog, or head to our Dive Shop Locator to find the dive shop for your Zanibar adventure!

Find out more about PADI’s involvement in environmental and community projects.

About the Author

Alex McMaster grew up on the rugged west coast of Ireland where the sea, mountains and forests cultivated his love for the wild. When these had been explored, he was drawn away on sailing expeditions in Oceania, Europe and the Arctic. Whether on the high seas or a trans-continental bike ride, he always has a dive mask to hand to find out what lies below the surface of a place. That ethos extends to his desire to know the intricacies of each point and person that he encounters on his journeys. Alex lives in Scotland, where he is a student.