On their recent expedition to Cocos Island, a global hotbed of shark activity, Mission Blue sat down with Randall Arauz, a lifelong marine conservationist and recipient of the Goldman Environmental Prize in 2010 for his efforts in protecting sharks and the banning of the shark finning industry in Costa Rica. What follows is a primer on why shark finning happens and how science can help stop it and inform sensible conservation management strategies. The questions were asked by Kip Evans, Mission Blue’s Director of Photography and Expeditions.

Could you describe the shark fishing and finning problem on a global level?

Shark finning is a global issue and it started in the 80’s when the long line explosion happened throughout the world and the fishermen saw that they could make a fortune off of shark fins. And the big issue is that shark fins cost $100/kilo for the fins, whereas the meat of the shark only costs 50¢/kilo. When you’re a fisherman, your limiting factor is your holding capacity. So would you rather bring your hold full of meat that is worth 50¢/kilo or shark fins that are worth $100/kilo? That’s the economic incentive to fin the sharks.

And this has been happening all over the world for decades. And the big problem is the Taiwanese businessmen come to countries like Spain, Costa Rica, Mexico, Ecuador – and they buy these fins from the domestic fishermen. And there’s a lot of money to be made, so the locals make a lot of money. And these shark fins get sent to Hong Kong, which is the hub of the Taiwanese shark finning industry. And from Hong Kong, they get distributed throughout Asia. It’s a huge operation. A multimillion dollar operation. And there have even been ties to local mafias in Asia that interact with this market. It’s very very lucrative.

Tell us about your work with shark finning in Costa Rica.

We’ve been working on the shark finning issue since 1997. We actually blew the whistle on what was going on in Costa Rica then. Unfortunately, when we figured out what was going on in 1997, the shark finning fleet from Taiwan had had 15 years of time to work here in Costa Rica, completely unchecked and freely finning sharks. Ever since, we’ve had a campaign to try to reverse the situation, first by creating laws and regulations against shark finning. Second, and perhaps the most important part, is implementation and making sure the regulations are respected.

What is the problem with the Taiwanese coming to a place like Cocos or fishing off other parts of the Costa Rican coast?

Back in the 80’s when Costa Rica invited the Taiwanese to come to Costa Rica, and throughout the region, the local fleets were fishing just off the coast. And as you know, Costa Rica has Cocos Island and this huge EEZ (Exclusive Economic Zone). Back then, politicians used to say that we “lived with our back towards the sea” and that we needed to exploit this huge resource, the Costa Rican EEZ, which is ten times bigger than the country itself. So the government of Costa Rica decided to invite a Taiwanese mission to train Costa Ricans how to long line in the open ocean.

But when the Taiwanese diplomatic mission came, they saw the wealth that could be made here on the shark fins. That’s when they decided to turn from technicians to businessmen. I can freely say they corrupted the Costa Rican government. Millions of dollars were involved; they invested money on improving infrastructure in Puntarenas. They did a boulevard in Puntarenas. They built docks and they actually became involved with the Costa Rican Fisheries Institute. And they pretty much got a grip on Costa Rican fisheries policy.

Tell me how the fins are processed through Costa Rica that the Taiwanese bring to shore.

The Taiwanese are operating throughout the Eastern Pacific, all the way from Mexico down to Northern Chile. And Costa Rica, for at least 20 years, was the hub of the shark fin industry. These boats are either Taiwanese flagged – or Belize or Panama flagged using flags of convenience – but all these boats were foreign boats. And because of that, these boats were supposed to use public facilities in which to land their products. In this way there could be accountability. Instead, for many years these foreign fishing vessels were free to operate and bring all the shark fins that they could from the whole region to their private processing plants here in Puntarenas. And then they would dry the fins and directly export them. And let’s remember that in 2001, Costa Rica was the third global shark fin exporter with close to 950 tons a year.

Tell me about how Fins Attached is trying to make a difference and get the laws changed in Costa Rica.

We already have the anti-shark finning law. And during our past administration with President Laura Chinchilla we were able to list hammerhead sharks under CITES (the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora). Now, the best thing would be if we could snap our fingers and get rid of the foreign fleets altogether, but of course, these people are very well ingrained in Costa Rica by now. They have lots of political sway and economic support. And so we’re trying to curtail this situation with the tools that are provided to us by international policy.

So, first we went with President Chinchilla to CITES and we were able to list hammerhead sharks on Appendix II, which will impose international regulations. We also recently worked to get silky sharks and thresher sharks listed. CITES is a great opportunity, but CITES by itself isn’t going to do anything. CITES is a tool that we as conservationists have to use to work with our governments to make sure these regulations are actually implemented. And that’s what we’re doing right now. We are literally breathing down the Costa Rican government’s neck. We are watching everything they are doing with the shark fin industry. And we are blowing the whistle because Costa Rica is doing everything possible under this new presidential administration of Solís to circumvent the CITES regulations.

And what we do is expose the situation, take the government to court, appeal to public opinion and ultimately try to avert this travesty that is occurring now in Costa Rica. Think about it: Costa Rica, the global conservation nation…and we’re also the shark finning nation and one that violates international conventions on endangered species.

Could you describe the tagging you are doing and explain how it can make a difference for the sharks?

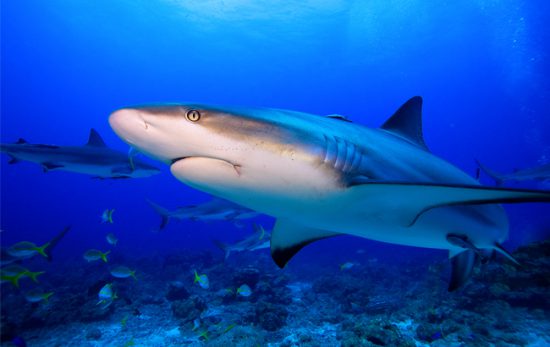

To save sharks in the Eastern Pacific, or anywhere in the world, we need to know where they are going. We know that sharks are highly migratory. But where are they going? We know they are not randomly distributed throughout the ocean. There are areas where sharks like to congregate and Cocos Island is one of them. Here, when you’re diving out at Manulita and you see all these hammerhead sharks, they aren’t distributed like that randomly throughout the ocean. There are very specific places where they do this – and they are called hot spots. Cocos Island is one. Galapagos is another.

But we need to know, for example, how are the sharks from Cocos Island relating to sharks in other hot spots like Malpelo Island off the coast of Colombia or Galapagos off the coast of Ecuador? Are they the same sharks? How do they relate to each other? Answers to these questions are very important for conservation management. And so we need to coordinate with different countries and see where the sharks are going. And that’s what we’re doing with the tagging.

And of course, with this tagging effort, we also need to collaborate with the researchers in the region. Because I could tag a bunch of sharks at Cocos Island, but if I’m not coordinating with the researchers at Galapagos or Malpelo, or on the mainland, we’re not going to know where these sharks are going. So this is really team work. And many researchers have to get together so we can figure this out. And that will be the only way that we can design real management plans and conservation plans. If we know where they are going and when they are going.

What do you see as the future of these sharks?

We have to be optimistic. Let’s remember that according to the science, we still have 10% of the sharks that we had 50 years ago. So we have to get busy. My goal is for all sharks in the future to enjoy this same protection that sea turtles currently enjoy, that is, total protection from international commerce.

Founder of Mission Blue, Dr. Sylvia Earle shares how we as divers can be a part of protecting and restoring our oceans during her recent trip to Cocos Island.

If your inspiration to start diving came from Jacques Cousteau, then Cocos Island should be on your radar: he considered Cocos Island to be the most beautiful island in the world. Read more about this Hope Spot here.