Since the 1970s, we’ve designated February as Black History Month. This month, in particular, represents a time to collectively commemorate the history and achievements of Black people. Additionally, it offers an invitation to look towards a more inclusive and equitable future.

The Origin of Black History Month

According to Brittanica, this tradition of celebrating African American culture in February actually began in 1915. Eminent American historian Carter G. Woodson encouraged scholars to “engage in the intensive study of the Black past.” In fact, Black history had been “sorely neglected” by academia or “distorted in the hands of historians,” he asserted. Furthermore, he noted that traditional and predominating views of Blacks in American and world affairs were “biased”.

Therefore, he pushed for these studies as a critical way to move forward by first examining the past.

Being Black in Diving

Currently, within the scuba diving world, we continue to honor Woodson’s intention by delving into what it means to be Black in the diving world. This introspection requires a closer look at the human toll of the transatlantic slave trade and the generational trauma that remains.

Diving with a Purpose conducted much of that difficult work. In fact, the group protects submerged heritage and marine conservation, especially as related to the African Diaspora.

Several PADI AmbassaDivers guide us through these conversations. From around the world, each has had a different experience being a diverse diver and ocean ambassador. Their stories help us understand and reconcile with painful truths from the past. Additionally, they offer suggestions on how we can support BIPOC and underrepresented communities. We must do so during Black History Month as well as during the rest of the year.

Dr. Tiara Moore: Marine Ecologist and Diversity Advocate

The Search for Belonging

When Dr. Tiara Moore describes her experiences as a Black diver and scientist, she notes a certain stigma. “There’s a feeling like we aren’t supposed to be there,” she says.

She recalls being the only Black person on her marine science teams and having others assume she’s there to carry the tanks or that she doesn’t know what she’s doing.

“It’s embarrassing to be called out like that,” she says. “Then disappointing. I worked this hard to get my certifications and I still don’t belong.”

The harmful stereotypes and assumptions persist due to the lack of diversity in diving and in science. These experiences, and how isolating they made her feel, led Moore to found Black in Marine Science (BIMS) at the end of 2020.

“For the first time, I found Black scientists all over the world. For the first time, I didn’t feel isolated,” she shares. “We may be the only Black person in our rooms, but now we see there are hundreds of rooms around the world.”

Healing Generational Trauma

Programs like BIMS are also critical to help heal the “history and trauma of black people and water,” Moore shares. “Black people don’t want to jump into the water with millions of our ancestors literally at the bottom of the ocean… It’s like we’re to blame that we’re not there, but there are so many barriers and so much trauma.”

Even after slavery ended, the harm to the Black community did not. For example, Moore’s grandmother described how white people would throw acid into pools in black neighborhoods. Therefore, she never felt safe in the water. “There’s so much generational trauma that gets passed down. So, who’s gonna teach me to swim if my grandma wouldn’t get in the pool cuz of acid?” Moore genuinely asks.

Because of this painful history, “BIMS does programs to get more Black scuba divers PADI certified and in the water,” she says. “It’s great, but we need more funding for more programs.”

The training and support need to continue and sustain well past certification so that new Black divers actually have the opportunity to use their new skills recreationally and for research, she emphasizes. “If you get certified but you don’t have any relationship to diving afterward, then what? I’m a Black diver, but am I?” she queries.

Moore suggests that large organizations that want to support BIPOC divers and scientists work with historically black colleges and universities and other trusted community partners. This helps ensure that no harm and no tokenization occur, Moore says. Additionally, leadership has to be transparent and have lots of conversations about diversity and the push for inclusion before bringing Black people into historically white spaces. Without this “prep work,” shock and fear can sometimes lead to toxic situations and unsafe spaces for Black people to enter.

Weldon Wade: Ocean Innovator, Explorer, and Educator

Eyes in the Water

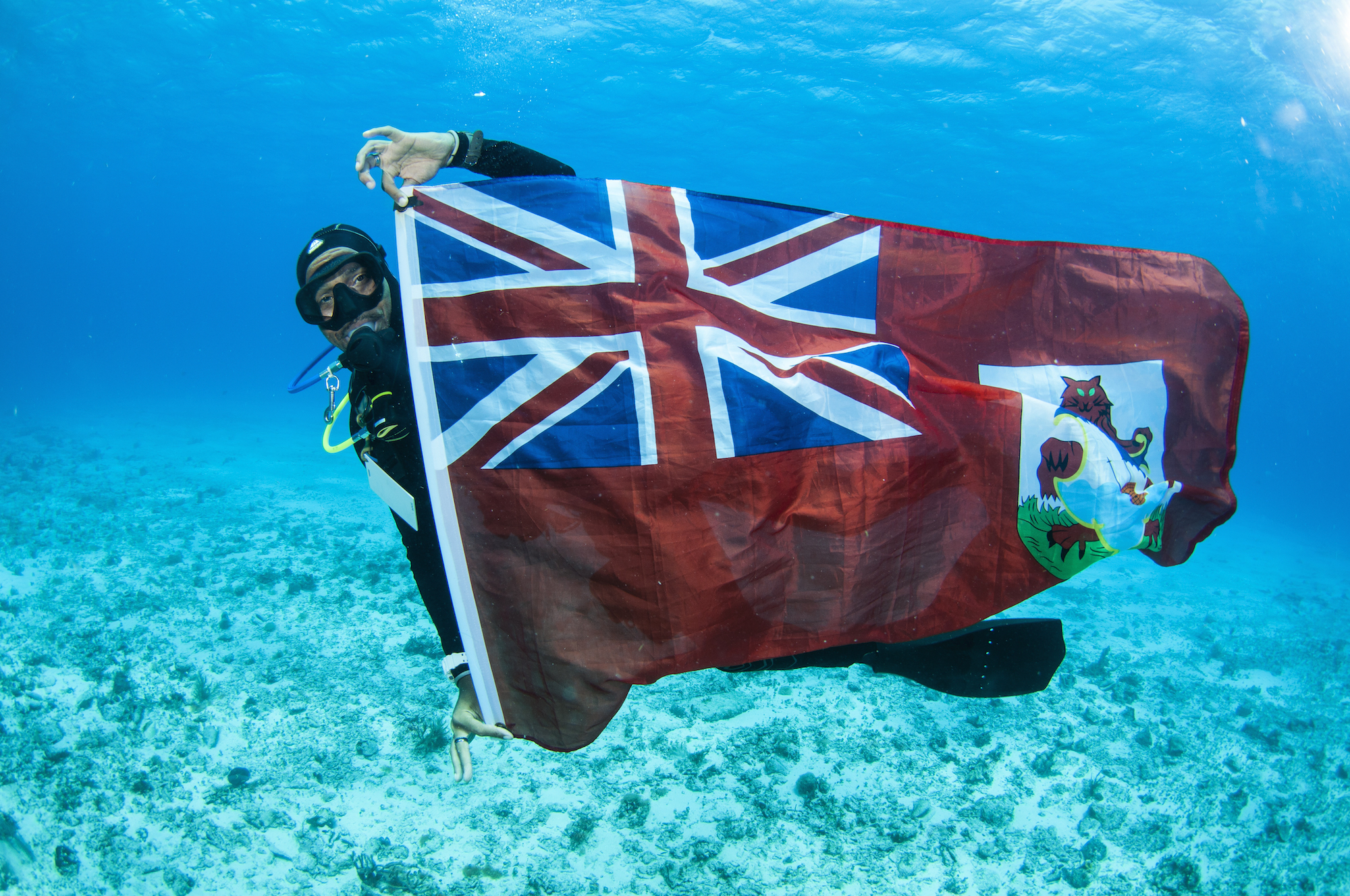

More than a decade ago, Weldon Wade – a Black Bermudian diver – noticed that he was often the only Black and Bermudian diver on local scuba boats. The majority of his community don’t swim or scuba dive, he realized.

To that end, Wade founded the not-for-profit Guardians of the Reef to facilitate getting kids and adults to “put their eyes underwater” to experience their local ocean and connect with it. In this way, he hopes to drive ocean protection and a new blue economy in Bermuda. He calls his role “super dope” because he gets to create purposeful diving experiences for his community to come together to do good for their environment. They participate in activities like Dives Against Debris and lionfish eradication to heal the ocean.

Building More Community

“Many feel like ocean recreation is reserved for a certain demographic, and it’s really not,” he says. “There might be barriers in the way” but those can be addressed. Often, the issue is not just financial, but also the lack of diversity on dive boats. “We go where we feel welcome, where we can go home and tell a dope story. If it doesn’t check those boxes, we don’t remain subscribed.”

To encourage more representation, Wade tells other Black divers to share their work and blue passion widely. In that way, they can continue building their community and helping the ocean.

Xochitl Clare: Marine Biologist and Performing Artist

Overcoming Barriers to the Ocean

“As a Latina African American with Caribbean heritage, the importance of life at sea is interwoven in my culture,” says Xochitl Clare. However, like many others, still experienced barriers to entry. Growing up in a single-parent, immigrant family, Clare couldn’t afford swimming lessons or marine science youth programs. Despite these challenges, her mother kept her aquatic dreams alive through ocean books and media.

Five years ago, Clare learned to swim as an adult in order to fulfill her scuba and marine science dreams. She cites her strong support network and mentors as critical to her success because they “remind [her] that [she] belong[s] in the water.”

What We Can Do

“Exposure, financial and access barriers continue to serve as the main limiting factors for increasing inclusion and diversity in scuba,” Clare says. “We, the PADI dive community, are well-positioned to engineer clear pathways and financial support for aquatic scholarship to diversify the next generation of ocean ambassadors to secure a brighter future.”

She adds, “To tackle environmental challenges and protect our blue backyards, we must involve individuals of all ethnic and socioeconomic backgrounds.”

Clare summarizes, “This work [of increasing diversity in diving] allows us to meet our history with the sea firsthand to contend with the past—to then charter a new future for African American communities in generations to come.”

Alannah Vellacott: Marine Ecologist and Science Communicator

Sustainable Diversity and Inclusion

“I recognize and it is a fact that, right now, Black and BIPOC is hot, and diversity is hot. Lots of companies are just jumping on the bandwagon,” says Alannah Vellacott. “But, what needs to happen is sustainable diversity. How do you build diversity into our plans and policies, as part of your 2022 ‘til forever goals?”

Vellacott, an Afro-Caribbean diver from the Bahamas, is accustomed to tokenization. Sometimes, she’s held up as the “representative of all Black people.”Often the only diverse diver on board, she never really “saw her reflection” in scuba and marine science careers. The same is true for other aspiring Black divers and scientists, Vellacott says. This is a problem.

“It’s very important to see yourself in your hobby of choice or in your dream career. It’s like, ‘Should I join this club?’ If you don’t see yourself and don’t connect with anyone, you don’t join the club,” she says. “But, if you come in and see people that look familiar, you think, ‘Maybe I can join too.’”

Uncovering Sunken Truths

As part of her own journey into her past, Vellacott joined Diving with a Purpose and Samuel L. Jackson for a six-part documentary series. Enslaved explores the transatlantic slave trade by diving the shipwrecks left behind.

“It’s about exposing the truths left unspoken or that we’ve never heard of,” Vellacott says.

CNN estimates that at least 1.8 million enslaved Africans died in oceanic crossings. “Who talks about that? Who’s mourning the lives of those people?” the news report asks. “We’ll never know their names, we’ll never know anything about them.”

This is a truth that haunts Vellacott and that made filming Enslaved sometimes difficult. Vellacott describes the complex, mixed feelings she had while filming an episode in Cornwall, UK, where her father is from. She feels elated to walk on the same streets her dad hung out on as a teenager. At the same time, she knew she was simultaneously exploring the atrocities that happened on her mom’s side.

She says, “I cried in every episode because it’s obviously painful, but it was especially painful for me because I’m biracial. My mom is Black and Bahamian, and my dad is English. It’s easy for me to trace my dad’s ancestry, but with my mom’s, without DNA testing, I get nowhere.”

Vellacott reminds us that slavery was a global phenomenon and not just an Americas problem. “Even the Pope blessed slavery,” she says. “It was just this upside-down time where the entire planet had no regard for human life that came from the continent of Africa.”

To move forward, we must continue this work so we don’t forget the lessons. She says, “History will repeat itself if you forget it. History doesn’t want to be forgotten, so it will repeat itself if we do forget…. We must never let anything like this happen ever again.”

Important Dive Sites/Shipwrecks Related to Black History

- “The Leusden” – Sunken off the coast of Suriname, the Leusden represents “the single greatest loss of life during the entire slave trade.” There were 640 Africans on board. Instead of trying to save them, the crew nailed down the hatches as the ship was sinking. This allowed the owners to make insurance claims for their “lost cargo” – the enslaved.

- A “Freedom Boat” – During slavery, many Africans and allies resisted. In The Great Lakes, a “Freedom Boat” is perfectly preserved. In fact, it ferried African Americans to freedom in Canada as part of the “Underground Railroad.”

- “Clotilda” – The Clotilda is the most intact slave shipwreck found to date. It is also the only ship for which we know the full story of the voyage, the passengers and their descendants. In July 1860, it carried 110 kidnapped Africans to slavery in Alabama. Afterward, the traffickers burned and sank the ship to mask their crimes.